|

Eleonora's Fabric in Bronzino's Painting"Eleonora and her son Giovanni" |

|

|

Eleonora's Fabric in Bronzino's Painting"Eleonora and her son Giovanni" |

|

The fabric that Eleonora wears in the famous painting is very striking and seemingly unique. It appears to be of a white satin background with black tendrils winding it's way around large bordered and small motifs of uncut velvet of gold.

Since 1857, the fabric as shown in the painting was thought to be the burial clothes uncovered from her grave in San Lorenzo, Florence. In 1986, a maverick of Historic Costume, Janet Arnold revealed and proved that the fabric Eleonora was buried in was actually a ground of charmeuse green satin silk (now faded pale yellow) with black embroidered bands; not an all over pattern of Cut and Uncut velvet.

However, the famous fabric may not be as unique as once was thought. In the last century, there have been many articles that have brought to light fabric and painting examples that bear a startling resemblance to the fabric of Eleonora. Consistent with all examples is the colour choices and the use of the pomegranate.

The pomegranate motif and colour choices seem to have been popular in Italy, England, and Spain. It also appears that Italy produced fabrics with the design for all European markets, even for the Ottoman Empire1. The stylistic design of the pomegranate seems to have symbolized fertility in period as put forward by Rosalia Bonito Ranelli.2

The examples are housed in museums all over Europe, with the exception of example 2 and 5. Bringing pictures of all these examples together in one location for comparison and study has allowed for some new ideas to be put forth.

Roberta Orsi Landini states the average width of a master artisan weaving was usually the length of the weaver's arm, especially if the weaver did not have anyone to help with the passing of the shuttle through the shed on the loom4. This usually amounted from 22 to 27inches. Luca Mola did indicate in his book that the standard width of all silks in Venice as well as other foreign market centers in Italy was 20-22 inches in 15505. Especially for the heavy silks and brocades. Juan Alcega, a Spanish Tailor in 1580-1590 in his treatise on garment patterns indicated that silk was woven to a width of 22 inches6. Many extant examples of fabrics from the 16th century do not have both selvages, but where there is at least one selvage, examples do seem to indicate that fabric designs were woven consistently to the selvages, so that continuous designs by sewing does seem possible.

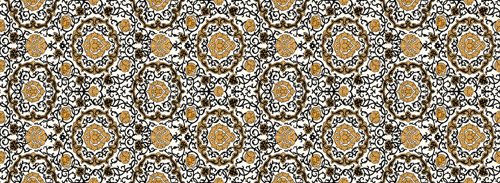

Having extrapolated a possible pattern and placement design with available research material, the finished fabric is conjectured thus:

At this point it becomes possible to recreate the repeater pattern and placement design on fabric with stensils and paint. Onwards to the Pattern Layout!

2) Bonito Fanelli, Rosalia

3)"Medici Project Turns Up Mystery Bodies" By Rossella Lorenzi

4) Martinis, Fabrizio De (ED)

5) Mola, Luca

6) Alcega, Juan de,

_

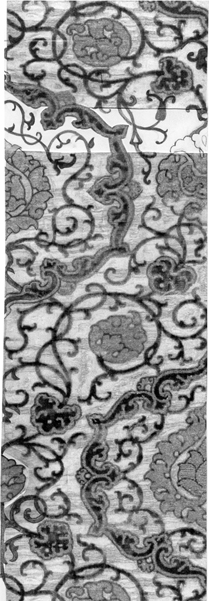

The fabric contained in the Civic Museum of Turin seems to be the closest match, but upon close inspection, there are some subtle style differences. The weave of the tendrils move in different directions and do not match up to the pomegranate motifs in the same places. The black borders are very similar, but the Turin example has more points. And the bed of leaves around the central pomegranate have a different size diamond shape on the bottom. There are several possibilities why this may be. The fabric of Eleonora may have been the "example" that workshops in Italy used to create close copies of. It is possible that both fabrics came from the same workshop, possibly in Spain, but not necessarily the same loom. It is also possible Eleonora's fabric only existed in the mind of the artist, Bronzino, who had a sample of the pattern from a Florentine loom. However the fabric was created, there is enough evidence available to cobble together the design of Eleonora's fabric to a reasonable degree of accuracy. Some written sources needed consulting in order to extrapolate the most accurate width, so that the repeater would be in correct proportion to the fabric.

The fabric contained in the Civic Museum of Turin seems to be the closest match, but upon close inspection, there are some subtle style differences. The weave of the tendrils move in different directions and do not match up to the pomegranate motifs in the same places. The black borders are very similar, but the Turin example has more points. And the bed of leaves around the central pomegranate have a different size diamond shape on the bottom. There are several possibilities why this may be. The fabric of Eleonora may have been the "example" that workshops in Italy used to create close copies of. It is possible that both fabrics came from the same workshop, possibly in Spain, but not necessarily the same loom. It is also possible Eleonora's fabric only existed in the mind of the artist, Bronzino, who had a sample of the pattern from a Florentine loom. However the fabric was created, there is enough evidence available to cobble together the design of Eleonora's fabric to a reasonable degree of accuracy. Some written sources needed consulting in order to extrapolate the most accurate width, so that the repeater would be in correct proportion to the fabric.

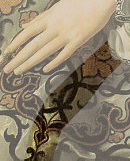

The skirt of Eleonora's gown seems to be continuous, however, underneath her left hand there is a thin black line that looks to be out of place. It could be a selvage seam, or a design element, or an artist's mistake. The black line disappears into the gold motif under her left arm. The attention to detail in the portrait suggests that this is not an artist's error. Since there does not appear to be any other mysterious thin black lines on the garment, it would seem unlikely it is a design element. It could most logically be a seam line. Possibly indicating selvage. The Turin example, along with example 4, do end off in the center of a leafy motif, indicating the ability to match up the design to create a continuous piece of fabric.

The skirt of Eleonora's gown seems to be continuous, however, underneath her left hand there is a thin black line that looks to be out of place. It could be a selvage seam, or a design element, or an artist's mistake. The black line disappears into the gold motif under her left arm. The attention to detail in the portrait suggests that this is not an artist's error. Since there does not appear to be any other mysterious thin black lines on the garment, it would seem unlikely it is a design element. It could most logically be a seam line. Possibly indicating selvage. The Turin example, along with example 4, do end off in the center of a leafy motif, indicating the ability to match up the design to create a continuous piece of fabric.

The Spanish Chasuble back seen as example 1 above, is actually a design in 3 pieces. It deceives the eye in this manner by matching up as closely as possible the design elements to look like a continuous piece of fabric.

The Turin example was placed in a computer graphic program and printed out. Using the black and gold rings on the design, the missing repeater section is spaced correctly. Using the portrait, the gap areas are filled in by hand. Since the Turin example is listed as (X by X), we can grid the sample and calculate a reasonable size for the complete repeater. Next, the burial bodice of Eleonora is examined and knowing her height of 5 feet3, a comparison is made between the repeater size and the bodice in the painting, and found to be very similarly sized. With the understanding that this is subjective and open to new interpretation, it would seem likely that the Turin example is a good reference with which to reconstruct this gown.

The Turin example was placed in a computer graphic program and printed out. Using the black and gold rings on the design, the missing repeater section is spaced correctly. Using the portrait, the gap areas are filled in by hand. Since the Turin example is listed as (X by X), we can grid the sample and calculate a reasonable size for the complete repeater. Next, the burial bodice of Eleonora is examined and knowing her height of 5 feet3, a comparison is made between the repeater size and the bodice in the painting, and found to be very similarly sized. With the understanding that this is subjective and open to new interpretation, it would seem likely that the Turin example is a good reference with which to reconstruct this gown.

Sources and Notes

1) Wearden, Jennifer

Sigmund von Herberstein: An italian velvet in the Ottoman Court"

Costume 19 1985 22-9

The Pomegranate Motif in Italian Renaissace Silks: A semiological Intrepretation of Pattern and Colour (IN)

"Cavaciocchi" "La Seta in Europa" PP 507-30

http://tlc.discovery.com/convergence/medici/news/medici/florence.html

Velvet, History, Techniques, Fashions.

Idea Books, New York (1994)

The Silk Industry of Renaissance Venice

John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (c) 2000

Libro de geometria, Pratica y Traca, 1589

Translated and published by V&A Museum, London

repr. Tailorís Pattern Book 1589

Costume & Fashion Press, New York-Hollywood (c) 1999