|

The Early History of the Spanish Farthingale |

|

|

The Early History of the Spanish Farthingale |

|

The farthingale has a murky past. First known to be named, "verdugada", it was rumoured to have started with the concealing of a pregnancy from an indiscretion by the Spanish Queen, Juana de Portugal. Even though it may have been true, the queen died in 1475, and the farthingale only begins to appear in paintings after that date. (1)

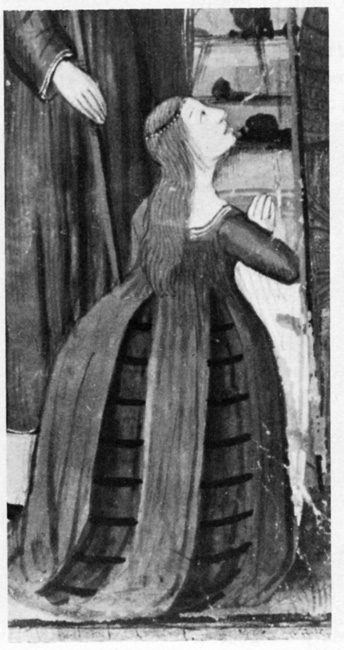

Early depictions of farthingales in Spain do not seem to have had a standard design, resting heavily on fashion tastes and regional differences. The hoops could be worn inside or out, under a skirt, as the skirt, or as a forepart. It was not even restricted to skirts; it was also used with Brials (tunics with cuffed, tight sleeves made from decorated silks or shot silks with gold). (2)

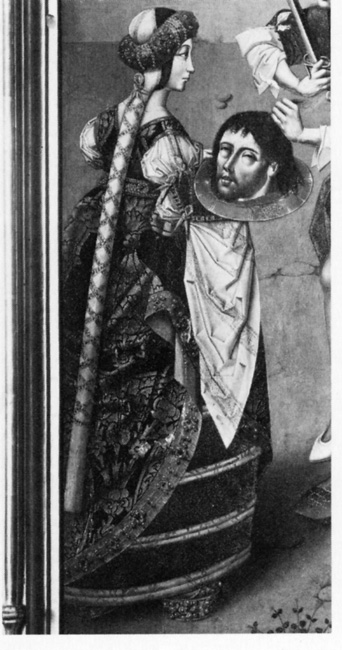

With time, and intermarriage, the farthingale lost its appeal in Spain both as an overgarment and as decorative hoops for the brial. By 1525, only lower class women and "undesirables" were still wearing farthingales on the outside as a fancy part of their attire.(3) However, the farthingale survived as a popular Spanish undergarment of the upper classes and nobility, becoming as popular in England, France, and (later on) Italy.

In Spain, farthingales were made out of many materials, silks, cloth of gold; encompassing all manners of colours, with weaves of taffeta, velvet, satin, damask, and brocade. (3) In England, Queen Elizabeth's accounts list silks, buckram, linen, and canvas, mostly of black and crimson colour, with weaves of stiff taffeta and velvets, trimmed or reinforced with kersey (a type of wool). (4)

At first there is written evidence that the stiffenings were made of osiers (willow branches), but pictorial evidence from the early 1500's indicate they were stiffened also with rope. Queen Elizabeth's early accounts indicate her farthingales were constructed with small ropes, stiff ropes, bents (osiers) and eventually, towards the end of her reign, whalebone. (5)

The pictorial accounts seem to indicate the stiffenings were held in place with strips of material sewn directly onto the skirt. These could be decorative also, usually with velvet. By the time of Alcega's Pattern Book, 1589, the farthingale's stiffenings (as conjectured by Janet Arnold) may have been held in place by tucks made in the actual skirt itself.(6)

By the turn of the century, most of Europe had adopted the farthingale as a standard form of dress, with the notable exeption of England who had reshaped the farthingale to the now familiar wheel farthingale. The new shape was adopted in France, but the wheel farthingale quickly lost popularity with the death of Queen Elizabeth, to be replaced with naturally flowing skirts with no serious understructure.

Bibliography

Bernis (Madroza), Carmen. (1955). Indumentaria Medieval Espasola. Madrid: Institute Diego Velasquez

Arnold, Janet (1988). Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlocked. London:Maney Publishers p 194-198

Anderson, Ruth M (1979). Hispanic Costume 1480-1530. New York: Hispanic Society of America p209

(1) Anderson, p 208

(2) Anderson, p 208

(3) Anderson, p 209

(4) Arnold, p197

(5) Arnold, p 198

(6)Arnold, p 197

_